Zen and Quaker practice: a sharing of spiritual paths and friendship

This article explores some of the background to Zen and Quaker traditions, annually brought together in the wonderful ‘Mindfully Together’ joint Zen-Quaker retreat, now in its twelfth year. In 2018 the retreat will, once again, be held at the Quaker Study Centre at Woodbrooke near Birmingham from 26th to 31st August, providing a wonderful opportunity for the Community of Interbeing (i.e. the followers of Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh) to come together with Quaker Friends in a complementary sharing of our spiritual journeys to nourish mutual understanding and shared insights.

Two Reforming Teachers: two traditions

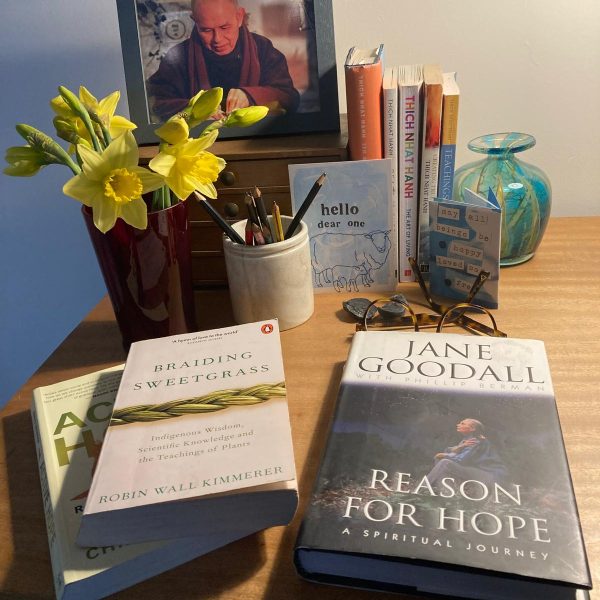

The founder of the Order of Interbeing is Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh (b. 1926, affectionately known as ‘Thay’ i.e. teacher), a great reforming teacher for modern times who has translated many Zen (Buddhist) teachings into highly accessible (western) forms. So determined was Thay to live in accordance with the ethical guidance and spiritual understanding of the Buddha (i.e. the ‘Awakened One’) that he came to the west on a mission for peace to try and halt the war in his home country of Vietnam. Unexpectedly forced into exile, he founded a thriving Monastic Centre called ‘Plum Village,’ in Southern France. This kernel has now grown into a large global community with followers, lay and monastic practitioners, and other monastic centres, across the world.

The founder of the ‘Society of Friends,’ also known as ‘Quakers,’ was George Fox (1624-1691), a great reforming figure of the 17th century. The Society arose in a Christian context and drew from that Christian heritage and the teachings of Christ (i.e. ‘the Anointed One’). However, so determined was George Fox to explore his own spiritual vocation and understanding of God free from the constraints of traditional Christian forms that he was viewed as a threat to the religious and political authorities at the time and was imprisoned on many occasions. In the present situation of interfaith dialogue and understanding, many ‘Friends’ draw on ethical guidance and meaning from other faiths.

These great reforming teachers share an unwavering service to their respective spiritual paths.

The two teachings ‘in practice’

In ‘Zen Practice’ practitioners gather in a group to sit either on a meditation cushion or on a chair (sometimes also to walk) in silence while supported by the gentle sound of a bell to ‘mindfully’ meditate, follow their own breathing and ‘dwell in the present moment.’ The practice of ‘mindfulness meditation,’ available to everyone, allows the ‘transformation’ of an individual’s suffering (under the practitioner’s own volition) and an ‘opening of the heart’ to love and compassion in the service of others. There is no God in Buddhism: the historical Buddha (the ‘Awakened One’) was a man called Siddhartha Gautama (c. 6th century BCE) who left us the Dharma (i.e. teachings). Understanding of the Dharma based on individual experience may be voiced (or not) in a ‘Dharma Sharing’ group. In order for the practice to be authentic, integral and engaged, the fruits of meditation need to be applied in daily life, in thoughts, speech and action.

‘Quaker Worship’ may vary from this in ‘form’ but Friends also gather in a group to sit on chairs in a comfortable room in silence. An individual’s understanding rests on the experience that a ‘seed’ of the holy, of God, rests in every person while they look to allow life to be guided by their own experience of the light of God. An opening to God can be discovered without a priest and the light of the Kingdom of Heaven is available ‘now’ in this world. Friends sit in gathered silence until ‘called’ by God to share (or not). ‘Ministry’ may come from anyone during worship so any member of the group may stand and speak. Sometimes no one speaks; a deep and profound silence can develop. There are many views of God amongst Friends, expressed in numerous ways while ‘God is love’ sits at the centre of understanding with an emphasis on humility and listening to others. Since infinite truths cannot be contained in finite words there are no creeds and a commitment to be honest at all times means that Quakers do not take oaths (which carry the implication that there may be times when lying is acceptable).

The practices of the two traditions share key features in common e.g. silent practice, respect for one’s own experience as well as that of others, equality of all, peace, social justice, community life and freedom of conscience. The natural environment is also hugely important with emphasis on simple living to minimise any impact on the world.

On Zen and Quaker writings

A series of writings underpin both traditions, which also have features in common.

In Zen, practitioners see the Dharma (the teachings of the Buddha) as deeply inspirational and a key to understanding (and therefore study the Dharma, attend Dharma talks and engage in Dharma Sharing) but may also read many other books including the Bible as a guide to their life and spiritual path. Meanwhile, underpinning Zen teachings are the ‘Five Mindfulness Trainings’ (i.e. precepts) taken by practitioners in support of their practice (common to all Buddhist paths) and provide an ethical basis for living life. These are to refrain from: harming living things, taking what is not given, sexual misconduct, lying or gossiping, and ingesting intoxicants.

Friends (Quakers) reflect their understandings in their main book ‘Quaker Faith and Practice,’ writings accumulated over almost four centuries that sit alongside the Bible and which are regularly revised to reflect new insights. ‘Quaker Testimonies’ are the forms of witness that have emerged from seeking to be open to the Spirit of God at all times. This has led them to emphasise: the adherence to truth (i.e. no lying); the principle of equality while embracing care for the whole of planet Earth (with all given respect and justice); simplicity of living (and rejection of greed); an embrace of peace (and rejection of killing) with action towards conflict resolution. Friends also have a tradition of literature known as ‘Advices and Queries,’ a short reminder of the insights of their Society, which each individual may personally consider particularly in relation to service. They regard the Bible as a deeply inspirational book but may also read many other sources and religious texts including Buddhist ones.

So striking has been the ethical and practice ‘overlap’ of the central Buddhist teachings of the Five Mindfulness Trainings with the Quaker Testimonies, as reflected in aspects of ‘Advices and Queries,’ that Audrey Urry (Quaker) and Lesley Collington (Zen Practitioner) have jointly produced a helpful booklet entitled ‘A Contemplation of Shared Insights: the Five mindfulness Trainings and Advices and Queries,’ which beautifully highlights the similarities of the two ethical approaches.

Observation from personal experience

In 2017, I (Harry) had the good fortune to attend this inspiring Zen-Quaker retreat. As a Practitioner in Thay’s Zen tradition but raised in the west within the Anglican Christian tradition, I found the more theistic language of Quaker Worship natural, meaningful and enriching while engagement with Quaker practices themselves resulted in fresh insights. During the course of the retreat, the notion of ‘two separate traditions’ gradually grew less apparent with a sense that exposure to the two ‘forms’ of spiritual practice can result in a deep complementary enrichment. I even speculated that if George Fox had perhaps been surrounded by the tradition of Buddhism (which in the seventeenth century was only known in the east) he may have been recognised as a Buddha and would not have found himself so much at odds with the morays of his time and place (bearing in mind that since the time of the ‘historical’ Buddha mentioned above, other individuals have also been recognised as Buddhas).

An invitation to practise together

The retreat is to be led by Sister True Virtue (Annabel), Head of Practice at the European Institute for Applied Buddhism in Germany, and will benefit greatly from her series of Dharma talks. She will be supported by both Zen monastics from Plum Village, Southern France and the Lay Order. Integrated into the retreat schedule, Quaker practices will include a daily morning ‘Meeting for Worship’ and (what is called) an evening ‘epilogue’ while a talk on Quaker practice will also be offered.

Finally, I can also report that the Quaker Study Centre at Woodbrooke is a beautiful venue, full of energy born of countless spiritual practitioners over many generations and provides comfortable accommodation, extensive gardens, a library, excellent food and a long-established tradition of welcome and service.

Overall, the retreat is a wonderful opportunity for us to come together, practise mindfully and engage in deep listening in our aspiration to ‘go as a river’ in relationship with others.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Tim P. Ashworth, Tutor in Biblical Studies and Interfaith Coordinator at the Woodbrooke Quaker Studies Centre, Birmingham, who kindly read and provided various re-wordings for the Quaker sections of this article.

Article by Harry Bradshaw (Dharma name: ‘Joyful Simplicity of the Heart’) and Lesley Collington (Dharma name: ‘True Lotus of Joy’) Zen practitioners and students of Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh.